Teaching the 2016 Election: Battle for Control of the U.S. Senate

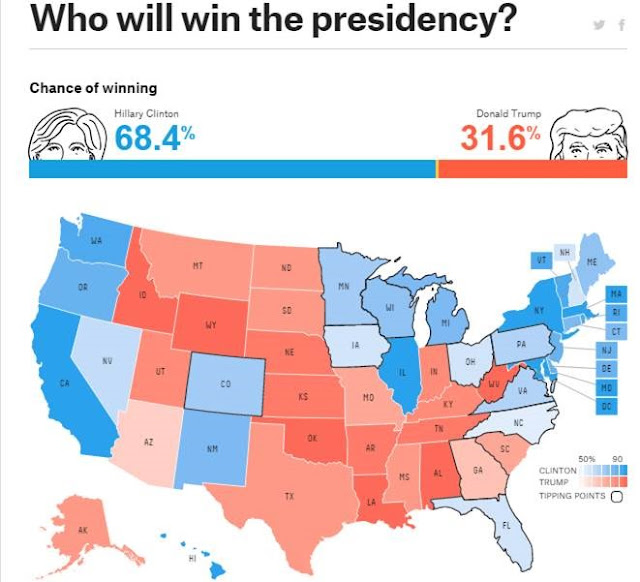

by Shawn Healy, PhD, Civic Learning Scholar In most presidential election years, we pay abundant attention to the battle for the leader of the free world, with good reason. In 2016, with both major party nominees historically unpopular , it’s quite possible that record numbers of voters will choose to sit this election out. That’s unfortunate for a number of reasons, including the other contested contests down the ballot, the battle for control of the U.S. Senate in particular. Republicans currently hold a 54-46 seat majority in the Senate. This is of course short of the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture to break a filibuster, but enough for control of the body and its committees. One-third of Senate seats are contested every two years, and 34 of them are at stake in 2016, 24 currently occupied by Republicans. Therefore, Democrats need only a net gain of 5 seats to retake the majority, or 4 should Hillary Clinton win the White House and her Vice President Tim Kaine be positione...