The New Political Normal Tests Teachers' Commitments to Neutrality and Impartiality

by Shawn Healy, PhD, Civic Learning Scholar

Current and controversial issues discussions are embedded in Illinois’ new civics course requirement and among the proven civic learning practices that help facilitate students’ civic development. Last summer, we raised the issue of whether teachers should disclose their personal views when facilitating these discussions and pointed to research that suggests both disclosure and nondisclosure can work so long as a safe classroom environment is maintained. The most recent presidential election and its frantic aftermath have further tested this formula, and it’s fair to say that as educators we’re still adjusting to the “new normal.”

Last weekend, I had the honor of attending the American Political Science Association’s annual Teaching and Learning Conference in Long Beach. While there, I attended a workshop led by Nancy Thomas of Tufts University where she explored the “neutrality challenge,” placing forth four different teaching approaches to addressing controversial issues in the classroom. The exercise assumed that social justice is the ultimate goal of civic or political education, admittedly a contested concept.

On one end of the spectrum, we were offered a pedagogical approach that places trust in the process of classroom deliberation. If done well, the process itself with produce social justice. In my experience and research, most educators adhere to this approach.

From neutrality we creep a bit closer to subjectivity, acknowledging teachers’ passion for certain issues, thereby drawing attention to something that concerns us, yet remaining agnostic about what should be done. The latter, once more, is left to student deliberation.

Intentionality enters the fray as we drift to the disclosure side of the spectrum. Thomas writes, “We need to be more intentional. What’s missing is an industry-wide commitment to a purposeful, explicit examination of patterns of power, privilege, and structural inequality underlying any public problem.”

The shift is completed when social justice is identified as “the work” itself. Thomas continues, “(Teachers) need to acknowledge that structural inequalities exist in society, these inequalities are detrimental to a strong democracy, and social, political, and economic justice are goals of the work.”

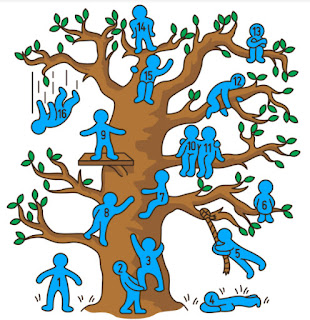

Thomas led participants through a four corners exercise as we identified with one or more of these perspectives. There was some subtle shifting as she raised different issues, from climate change to sexual assault to President Trump himself, suggesting that there may be a situational aspect to this pedagogical decision.

Also surfaced was the need to account for the perspectives and identities of our students. However, one attendee made a good point in saying it’s not equivalent to balance one student’s political views with another’s personal identity as is true in the current debate over President Trump’s Muslim ban, for example.

Finally, I raised the issue that geographic context also matters. It is a safe decision to go all in on social justice in deep blue Chicago, but tougher in the more politically heterogeneous suburbs, and perhaps a career-ender in some conservative downstate communities.

In sum, I appreciate the complexity of the model offered by Thomas and look forward to your own thoughts on its application. As we collectively navigate what seem like unprecedented political times, I find it helpful to reexamine current practices and place our best foot forward for our students.

Comments

Post a Comment