In Search of Oases in Civic Deserts

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

Last week, I had the honor in participating in the National Conference on Citizenship in Washington, D.C. For the past decade-plus, the congressionally-chartered organization has published annual reports on the nation’s civic health. The McCormick Foundation has been a proud local partner, producing state and local civic health reports of our own, and also providing funding for this year’s national publication, Civic Deserts: America’s Civic Health Challenge.

Civic deserts are defined as “communities without opportunities for civic engagement” and are increasingly common in rural and urban areas alike. More broadly, our nation’s civic health is in a continued state of decline, posing existential threats to “our prosperity, safety, and democracy.”

- A little more than a quarter of us (28%) belong to a group led by individuals we consider accountable and inclusive.

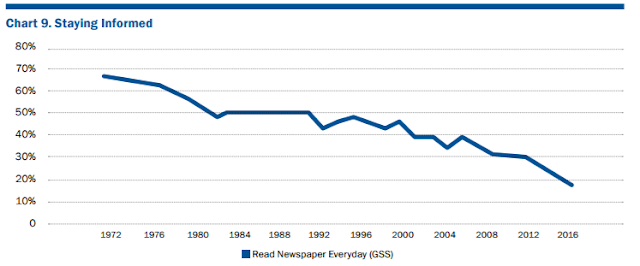

- Large-scale civic institutions like political parties, labor unions, metropolitan daily newspapers (see Chart 9 below), and religious congregations continue to shrink. They formerly mobilized communities for civic and political purposes.

- Declines in newspaper readership are coupled with plummeting trust in all forms of news media.

- Volunteering rates have fallen from already low percentages, dropping from 30% in 2005 to 25% in 2015.

Per recent trends, this report places part of the blame for our civic deficits on the marginalization of civic learning in P-20 education. The authors (Matthew Atwell, John Bridgeland, and Peter Levine) point to the decline of civics course offerings, specifically problems of democracy classes, and recipient waning student performance on sporadic administrations of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in Civics. Even among the upper echelon of high school students, the percentage taking AP U.S. Government and Politics has declined precipitously over the last quarter century.

I encourage you to read the report in full for a comprehensive view of our contemporary civic health crisis, but will conclude by riffing from the “paths to civic renewal” provided by the authors, in particular their call to “increase access to and the quality of American history and civics education in the United States.”

This includes adoption of “rigorous state standards” as we have in Illinois, “meaningful assessments” (still work to do here), and coursework that features discussions of current and controversial issues and service learning (see our new high schools civics course requirement). Federal funding is also key, including the revival of the Teaching American History grant program, increased frequency of the NAEP Civics Assessment, and “disaggregated or state level data of the results.” The final recommendation parallels our own Democracy Schools Initiative, where schools that demonstrate deep commitments to civic learning and American history would receive “blue ribbon” federal recognition.

Comments

Post a Comment