Middle School Leaders Claim Civic Learning Marginalized in Their Buildings

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

As legislation to require middle school civics (House Bill 2265) moves through the Illinois General Assembly, the Illinois Civics team is partnering with the Center for Information Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University to determine the presumptive implementation needs of teachers, schools, and districts through a survey distributed earlier this month. We encourage middle school social studies teachers and administrators to weigh in and complete the survey by mid-May.

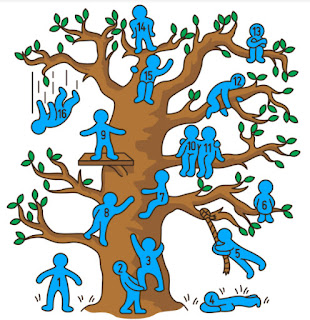

The need for middle school civics is profound. Only 23% of 8th graders demonstrated proficiency in civics on the 2014 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), with a stark civic achievement gap evident along racial and ethnic lines (see below). This coincides with a report from the Council of Chief State School Officers that 44% of school districts have reduced time spent on social studies since the advent of No Child Left Behind in 2001.

School leaders concur that the social studies, and civic learning specifically, have been unfairly and dangerously marginalized in an era where what is tested is taught. Last spring, Education Week surveyed 524 school leaders nationally about the state of civic learning in their districts. Fifty-seven percent of middle school leaders contended that their schools spend too little time on civic learning (not a single respondent said “too much”). And only 23% of middle school leaders reported that their schools offer a stand-along course in civics.

House Bill 2265 prescribes a mix of teacher-led and student-centered civic learning practices including direct instruction, discussion, service learning, and simulations of democratic processes in alignment with what school leaders consider most important. According to the Education Week survey, K-12 school leaders prefer current events discussions, instruction on the Constitution and related civil liberties, and modeling civic participation and voting.

Given the value that K-12 school leaders place on civic learning, they rank the pressure to focus on other tested subjects as the greatest challenge. The intensity of this pressure is most pronounced in middle and elementary schools.

A related challenge is that civic learning is not a district or school priority. A lack of civic learning resources and the political, controversial elements of civics present lesser challenges. Student interest, and somewhat surprisingly, teacher training, are deemed the least challenging among the survey options listed.

As demonstrated in my January post on the Civic Education System Map published by the CivXNow Coalition, the way civics is taught can help change public perceptions about its importance. In turn, public support drives state and district policies and related prioritization. The curricular mix embedded in House Bill 2265 will help propel a virtuous cycle, directly addressing the challenges surfaced by K-12 school leaders in the Education Week survey.

Overall, these findings underline the need to drive high-quality civic learning opportunities down to the earlier grades. We look forward to collecting the analyzing the Illinois-specific data from our middle school civics survey currently in the field in the months ahead to design an implementation plan responsive to the needs of teachers, schools, and districts in our demographically and geographically diverse state.

Comments

Post a Comment