Current Public Health and Economic Crisis Necessitates Urgent Equity in Civics Conversations

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

During the current public health crisis, educators are scrambling to move lessons online for students while balancing the numerous needs of our own families. The pedagogical conversations I participated in assume a middle-upper class perspective given our socioeconomic status. I would argue that we are blind to the needs of many of our less privileged students and their families who may instead be in survival mode and at a minimum don’t have one-to-one access to technology or high-speed internet connections. This lack of privilege is a product of structural inequities facing many of our students’ families.

I am honored to serve on a national Equity in Civics steering committee led by Generation Citizen and iCivics, and during a virtual meeting last week, my friend and colleague Amber Coleman-Mortley, Director of Social Engagement at iCivics, raised a profound point. She said that much of the current K-12 educational infrastructure is designed to work around parents, as schools typically connect educators directly with students. The current crisis scrambled this equation and laid bare fundamental inequities related to family engagement that break decisively by race and ethnicity, surfacing a longstanding equity challenge.

To illustrate this challenge, my final analysis of 2019 student survey data from a pilot group of eleven Illinois Democracy Schools (N=3,904 students) will address family background questions, with responses disaggregated by race/ethnicity. Previous installments addressed the degree to which students experienced civic learning opportunities and school cultures aligned with a “lived civics” framework, media literacy opportunities and outcomes, and the extent to which civic learning is threaded across the curriculum at selected Democracy Schools.

Students’ civic knowledge and skills, as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress in Civics, are impacted by their race/ethnicity, school lunch eligibility, language proficiency, and maternal educational attainment, with white, non-school lunch-eligible, native English-speaking sons and daughters of college graduates outperforming their less privileged peers (see Essential School Supports for Civic Learning, Chapter 5). Each of these variables exerts an independent force on student performance, and in many cases, issues of race/ethnicity, poverty, language proficiency, and social class are intersectional.

Educational attainment is used as a proxy for social class given the strong relationship between education and class. Maternal education attainment, rather than parental attainment, is preferred given the high percentage of single parent families and tendency for children to live with their mothers.

I disaggregated students’ maternal educational attainment by race/ethnicity at selected Illinois Democracy Schools and the differences are profound. The maternal educational attainment for the vast majority of Latinx students is high school or less (63%), compared to fewer than one-in-five white students (19%; see Figure 1). A plurality of Black mothers attended some college (37%), whereas white (37%) and Asian (30%) mothers peak at college graduation. Moreover, nearly one-in-five white (19%) and Asian mothers (18%) hold graduate degrees, far outpacing Latinx (5%) and Black mothers (11%).

In public presentations, I often lament that I am the face of civic engagement in America: white, highly educated, middle-upper class, and a native English speaker. As these features are pulled away, one is often exponentially less likely to engage civically in our democracy, particularly in measures beyond voting. Our data from selected Democracy Schools supports this claim, as a plurality of both Asian (27%) and Latinx students (37%) reported that their parents/guardians never engage in political activity (see Figure 2). By comparison, two-thirds of Black students (67%) and three-quarters of white students (76%) reported familial political engagement at least once a year.

Dinner table conversations about community and world affairs are considered a staple of civic engagement, and while more common than familial political engagement, also break decisively along racial and ethnic lines (see Figure 3). Whereas a plurality of Latinx and Black students are neutral in response to the question (both 35%), “In my house, we talk about what’s happening in our community and the world,” a plurality of Asian (35%) and white students (36%) answer in the affirmative. Moreover, white students are the only racial/ethnic group with an above-average percentage who “strongly agree” (24%; 21% average).

Please know that this post is not meant to cast blame or dispersions, nor do I pretend to have ready answers to the challenges surfaced in the charts above. Instead, I hope to inspire reflection and a conversation where issues of equity are central. These issues are by no means new, but warrant urgent attention in this moment of social distancing and economic dislocation.

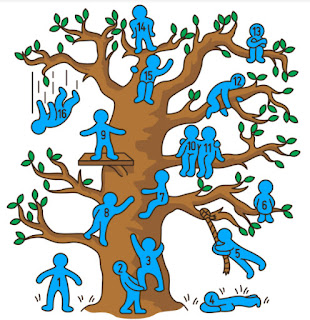

We must recognize that students come into our classrooms with varying definitions of familial civic engagement and related engagement experiences. We must also recognize and leverage the fundamental assets that students and families of color bring into our classrooms and schools, underlining once more the importance of a “lived civics framework” to designing cross-curricular and schoolwide civic learning opportunities. Starting lines are fundamentally staggered by race/ethnicity. More can be done to engage parents in the process of the civic development of their children, and the current moment forces the issue, providing our field with opportunities to engage students and their families in different, better, and more equitable ways.

Comments

Post a Comment