Racial Disproportionality of Student Punishment Impedes Progress on School Discipline Reform in Illinois

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

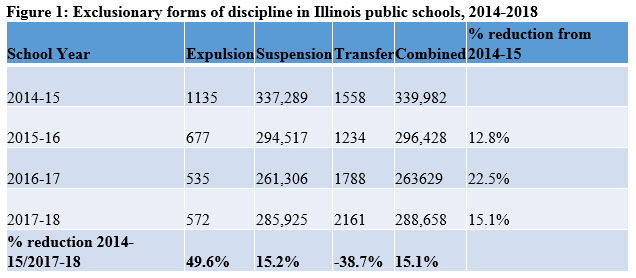

Since 2014, Illinois has been on the leading edge of school discipline reform. Thanks to the tireless advocacy of our partner Voices of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE), the General Assembly passed a series of laws that:

- Require districts to report exclusionary discipline measures (expulsions, suspensions, and transfers to alternative schools) by student subgroups, including race and ethnicity;

- Eliminate broad-based zero tolerance policies in favor of restorative practices;

- And prohibit preschool expulsion from state-funded facilities.

Despite this commendable progress, the central intent of the law, to reduce racial disparities in student punishment, has yet to be achieved. In 2014-2015, Black students represented 44.9% of those expelled, suspended, or transferred, despite composing only 17.5% of the state’s K-12 student population. This equates to a disproportionality factor of 2.6.

Fast forward to 2017-2018, Black students composed 43.2% of combined exclusionary discipline targets, but only 16.8% of the student population. The rate of disproportionality has held constant at 2.6 (see Figure 2 below).

Students identifying with two or more races are also more likely to face forms of exclusionary discipline than their percentage of the population would predict, while Latinx and white students are less likely, the latter significantly so.

These alarming findings provide further evidence that public policies present opportunities more than predict outcomes. Implementation, or lack thereof, is where policies succeed or fail.

It’s important to note that several our partners, including the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, have led the way on this front, ensuring compliance by ISBE and training administrators throughout the state.

These efforts should continue, but we must do more to engage other key stakeholders, teachers in particular. As humans, we all hold implicit biases, even though the vast majority of us as avowed anti-racists. These biases play out in our daily interactions with students and likely lead to inconsistent application of disciplinary practices in schools. This is especially true for students that bring significant trauma into our classrooms, trauma that most of us are poorly equipped to understand and manage.

Moreover, like the criminal justice system as a whole, we tend to employ a more carceral security apparatus in schools disproportionately serving students of color in urban environments. Herein lies the root of the school-to-prison pipeline, in many ways a preordained outcome given the intersectionality of implicit bias, trauma, and robust policing of certain schools.

We must do better as a state, for this discriminatory system undermines our efforts to foster positive civic development of students across gender, race, class, sexual orientation, and geography. Schools are public institutions, and their climate provides students with daily lessons on democratic governance, for better, and too often, for worse.

I therefore challenge ISBE to implement this law with fidelity, ensuring universal reporting of exclusionary punishment data by all demographic variables, especially race. It should also hold districts with high rates of disproportionality accountable for developing remedial plans.

I implore school administrators to pursue trainings like those led by the Chicago Lawyers Committee to better understand relevant statutes and most importantly how to move from exclusionary discipline to restorative practices.

And I encourage teachers to learn more about implicit bias and how it impacts our expectations for and interactions with students of color. As a member of the philanthropic community, the McCormick Foundation commits to identifying training opportunities and resources to assist with this and the aforementioned challenges.

Comments

Post a Comment