Illinois Democracy Schools Largely Embracing Lived Civics Principles, but Civic Empowerment Gap Persists

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

Since 2006, the Illinois Civic Mission Coalition, convened by the McCormick Foundation, has recognized 74 Illinois high schools as Democracy Schools. The recognition process has evolved significantly, broadening civics to a cross-curricular priority, measuring the organizational culture undergirding students’ civic learning experiences, and most recently, centering racial equity through a lived civics framework and disaggregating student survey data by race/ethnicity.

This spring, eleven members of our Democracy Schools Network piloted a revised student survey and schoolwide assessment process. What follows is a summary of trends in the student survey data, disaggregated by race (read the full analysis of questions related to lived civics).

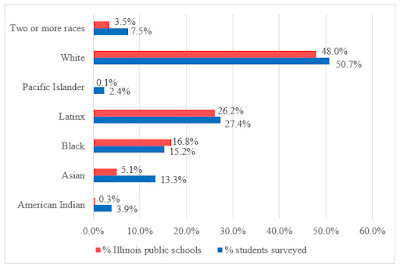

The sample of 3,904 students was broadly representative of Illinois’ demographic and geographic diversity. White and Latinx students were slightly overrepresented, and Black students underrepresented. Students of two or more races, Asian students, Pacific Islanders, and American Indian students were significantly overrepresented. Because students were allowed to select more than one racial/ethnic identification, all racial subgroups may be modestly overrepresented.

The sample of 3,904 students was broadly representative of Illinois’ demographic and geographic diversity. White and Latinx students were slightly overrepresented, and Black students underrepresented. Students of two or more races, Asian students, Pacific Islanders, and American Indian students were significantly overrepresented. Because students were allowed to select more than one racial/ethnic identification, all racial subgroups may be modestly overrepresented.Students were asked a battery of questions about the design of their classes and teaching strategies used within. For the most part, students rated their courses highly through the lens of lived civics, but there remains significant room for growth. For example, the vast majority of students (76%) report learning about the culture and history of people from different racial and ethnic backgrounds “sometimes” to “often,” yet white students are most likely to select “often.”

Fewer students reported learning about “people like me that are making or have made a difference in (their) community,” nearly two-thirds (65%) suggesting “rarely” to “sometimes,” but Black and Latinx students are the highest among those who selected “often.”

Similarly, most students are neutral to in agreement (69% combined) that teachers make time in class to discuss important issues in their community, with Black and Latinx students more likely to be neutral than their white and Asian peers.

On measures of school climate, students provided more mixed reviews across a battery of questions, exemplified by their neutral-to-agreeable (65% of students) response to, “Adults in my school treat all students fairly regardless of background or identity.” Mirroring concerns about disproportionality in exclusionary discipline by race/ethnicity, Black and Latinx students were most likely to offer a neutral response to this question and least likely to agree strongly.

Turning to student voice, a plurality of students (35%), led by Black and Latinx students and students of two or more races, are neutral when it comes to their ability to express views and highlight important issues through the school newspaper or student media. However, white and Asian students are significantly more likely to agree and agree strongly in response to this question.

When it comes to political action and expression, most students are on the proverbial sidelines, the exception being an even split between students saying that they have participated in a decision-making process at school. Black and white students were disproportionately more likely to answer this question in the affirmative and Latinx students in the negative.

Half of students reported volunteering in the community, but Asian (57%) and White students (59%) are significantly more likely to say “yes,” and Black (40%) and Latinx students (45%) “no.”

Upon turning 18, the vast majority of students (72%) plan to vote regularly, but white students (77%) are significantly more likely to answer in the affirmative. By comparison, students of two or more races (28%) have dramatically higher numbers answering in the negative, with students of color across the board more likely to report uncertainty.

Finally, across multiple measures of cognitive engagement with politics, Black and Latinx students shared less agreement, and more neutrality, than their Asian, and especially white peers. For example, when asked if “…by participating in politics I can make a difference,” Black, Latinx, and students of two of more races were more likely than white and Asian students to answer neutrally, while the latter two groups led among students in agreement.

In summary, our sample of Democracy Schools have strong evidence that a lived civics curriculum is taking root, yet there is significant room for growth, and a need to ensure that civic learning opportunities are offered equitably to all students. Schools should pay attention to inequitable opportunities and experiences with respect to student voice and school climate for students of color, Black and Latinx students in particular. Schools’ overall middling performance in these two categories make them priorities for the larger Democracy Schools Network to address.

The most alarming findings in this survey are evidence a stubborn civic empowerment gap across a range of measures of students’ current and prospective civic engagement. Equal inputs don’t necessarily translate into equal outcomes, highlighting the important distinction between equality and equity.

What can be done to make the quantity and quality of civic learning opportunities more equitable across race and ethnicity? And to what extent might school climates failing on measures of inclusivity and nondiscrimination undermine the benefits of relatively equal civic learning opportunities?

Future data analysis and posts will attempt to begin answering these questions, as will teachers and administrators within our Democracy Schools Network as we collectively work to eliminate the civic empowerment gap.

Comments

Post a Comment