Assessing the Strengths and Weaknesses of the #CivicsIsBack Campaign

by Shawn P. Healy, PhD, Democracy Program Director

Two weeks ago I introduced a summative report on the #CivicsIsBack campaign produced by the Center for Information Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University titled “Building for Better Democracy Together,” and last week I reviewed the impact of the campaign on teachers, schools, students, and our civic education nonprofit partners. This third installment of a five-part series will review CIRCLE’s overall assessment of our civics course implementation model.The report’s authors concluded,

The primary strength of the model is that it created a grassroots movement for transforming teaching practice in high school civics and enlisted a corps of teachers to be role models and experts to help other teachers also grow and learn to adopt best practices in civics instruction.

More specifically, implementation was delegated regionally to Illinois Civics Teacher Mentors with strong central support from Instructional Specialist Mary Ellen Daneels, who one partner described as a “superhero” and “amazing.” I couldn’t agree more.

Moreover,

Through a preliminary landscape analysis, we found a dearth of formal civics professional development opportunities, related financial constraints, and limited administrative support. The “secret sauce” of the #CivicsIsBack Campaign was thus access to free, flexible, and ongoing teacher professional development opportunities in every Illinois region. The report’s authors concluded, “We believe this comprehensive definition of ‘accessibility’ separates Illinois from other similar initiatives.”

By Year Two of the Campaign, Mary Ellen Daneels joined the Illinois Civics team as a full-time consultant, delivering customized professional development (PD) opportunities to local districts throughout the school year in addition to multi-day regional workshops in the summer. CIRCLE deemed the collective offerings as “exceptional” in that they were “research-based, experiential, scaffolded, and personalized.”

The authors crowned the McCormick Foundation “…the anchor institution for the statewide efforts to bring and sustain Civics in Illinois.” Credit is due to McCormick’s senior leadership, namely former President and CEO David Hiller and the Board of Directors, for supporting the #CivicsIsBack campaign from its inception through policy advocacy, funding commitments, and centralized programming.

PD was premised on both the “how” and “why” of implementing the civics course requirement and social studies standards. Even though both were enshrined in law, we never took the “why” for granted, presenting strong empirical evidence supporting the integration of student-centered practices into civics and social studies courses. Equally important were the “Monday morning lesson plans” demonstrated by Mary Ellen and the Mentors, where participating teachers engaged in lessons as students and left equipped to replicate them and the practices they embodied.

A final strength was the partnerships we built with colleges, universities, regional offices of education, and individual school districts as PD hosts and sites to institutionalize our work long-term, and as mentioned in last week’s post, civic education nonprofits specializing in teacher PD and related curriculum development.

A primary weakness of the #CivicsIsBack Campaign was its singular reliance of Mary Ellen Daneels as its central pillar, producing an unsustainable workload for her, and a herculean task should other states replicate our efforts.

Another weakness was the lack of attention to culturally sustaining pedagogy:

We also naively asked too much of Teacher Mentors, full-time educators with personal and professional responsibilities to balance. Moreover, Mentor contributions varied tremendously, and the rather large cohort proved difficult to manage. There is also healthy skepticism about our ability to support Mentors beyond the defined implementation period.

Finally, while teachers listed time constraints as the biggest implementation barrier, more could have been done to build grass-tops buy-in from leaders at the school, district, regional office, and state levels.

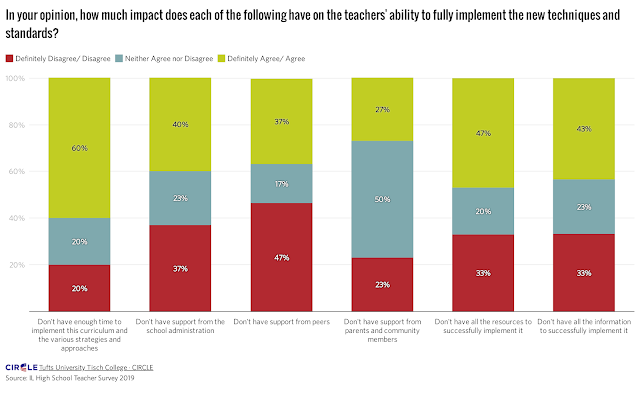

As is clear in the graph above, additional work remains in building support for civic learning among peers in the teaching profession and parents and community members. In a nod to the sustainability challenges to be addressed in next week’s post, too many teachers still lack the resources and information necessary to successfully implement the course and standards.

Apart from the fact that the peer mentors were teachers that understood what it meant to translate the mandate and standard requirements in classroom practice; it also mattered that they were local teachers who understood the regional context in such a diverse state.

Through a preliminary landscape analysis, we found a dearth of formal civics professional development opportunities, related financial constraints, and limited administrative support. The “secret sauce” of the #CivicsIsBack Campaign was thus access to free, flexible, and ongoing teacher professional development opportunities in every Illinois region. The report’s authors concluded, “We believe this comprehensive definition of ‘accessibility’ separates Illinois from other similar initiatives.”

By Year Two of the Campaign, Mary Ellen Daneels joined the Illinois Civics team as a full-time consultant, delivering customized professional development (PD) opportunities to local districts throughout the school year in addition to multi-day regional workshops in the summer. CIRCLE deemed the collective offerings as “exceptional” in that they were “research-based, experiential, scaffolded, and personalized.”

The authors crowned the McCormick Foundation “…the anchor institution for the statewide efforts to bring and sustain Civics in Illinois.” Credit is due to McCormick’s senior leadership, namely former President and CEO David Hiller and the Board of Directors, for supporting the #CivicsIsBack campaign from its inception through policy advocacy, funding commitments, and centralized programming.

PD was premised on both the “how” and “why” of implementing the civics course requirement and social studies standards. Even though both were enshrined in law, we never took the “why” for granted, presenting strong empirical evidence supporting the integration of student-centered practices into civics and social studies courses. Equally important were the “Monday morning lesson plans” demonstrated by Mary Ellen and the Mentors, where participating teachers engaged in lessons as students and left equipped to replicate them and the practices they embodied.

A final strength was the partnerships we built with colleges, universities, regional offices of education, and individual school districts as PD hosts and sites to institutionalize our work long-term, and as mentioned in last week’s post, civic education nonprofits specializing in teacher PD and related curriculum development.

A primary weakness of the #CivicsIsBack Campaign was its singular reliance of Mary Ellen Daneels as its central pillar, producing an unsustainable workload for her, and a herculean task should other states replicate our efforts.

Another weakness was the lack of attention to culturally sustaining pedagogy:

Some interviewees noted that more explicit focus on equity despite diverse students’ needs would improve the initiative, meaning that more focus was needed to promote the use of culturally-responsive pedagogy in conjunction with those practices to ensure that students of all backgrounds benefit equally from the initiative.

Finally, while teachers listed time constraints as the biggest implementation barrier, more could have been done to build grass-tops buy-in from leaders at the school, district, regional office, and state levels.

As is clear in the graph above, additional work remains in building support for civic learning among peers in the teaching profession and parents and community members. In a nod to the sustainability challenges to be addressed in next week’s post, too many teachers still lack the resources and information necessary to successfully implement the course and standards.

Comments

Post a Comment